Housing plays an important role in the health of a city. High vacancy rates can spell disaster on a sociological and economic level. It’s considered a bellwether for the strength of the economy. It’s why voters are concerned about properties with high vacancy rates across the city.

A report released on October 20 indicates that there are now 60,000 vacant units in San Francisco — far more than February estimates of 40,000. If there are so many reasons to keep vacancy rates low, why are so many units in San Francisco currently empty?

Housing supply, vacancy rates, and the cost of rent

When tenants move out of San Francisco, their units become available. If the unit was certified for occupancy before 1979, it is eligible for “vacancy decontrol.” Vacancy decontrol lets landlords reset the initial rent to whatever they want when renting the unit again. This severely impacts low-income renters because programs like Section 8 use neighborhood rental rates and determine their fair-market housing prices. Normally, property owners seek to fill these vacancies rapidly, but a recent report from ProPublica explains that new technology like RealPage uses an algorithm to convince managers they would make more money if they keep these units vacant to raise rent and make the market seem more stressful for tenants.

People leave San Francisco for many reasons, primarily because of job opportunities and housing costs. As the city’s biggest employers continue mass layoffs, job-seekers may head elsewhere. Renters who wish to buy a home know that properties are cheaper outside of major cities. With remote work offering tech workers more flexibility, thousands have left. These factors would ordinarily mean a higher vacancy rate, give renters more options, and encourage landlords to fill vacant units to keep cash flowing. However, San Francisco has many unique factors in play.

Rent control and tenants’ unions frighten avaricious landlords, and developers are heavily incentivized to build luxury housing. The implications of redlining endure, causing everything from health issues to increased segregation. Since it is cumbersome to change existing policy, remnants of redlining still affect what neighborhoods can do.

There are vacancies in San Francisco because the units are too expensive,” says Maria Zamudio, the organizing director at the Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco. “With so many high-earning tenants leaving the city … the demand for artificially inflated rent prices isn’t there.” This is on top of adding the impact of algorithms like RealPage’s that cut out overly “empathetic” leasing agents.

Several property managers have buildings with significant vacancy rates, including some with direct links to analysts at RealPage. A case study of Parkmerced, a popular off-campus housing option for college students, illuminates how the logic of vacancy rates has changed. To students, Parkmerced advertises there’s overwhelming demand. To investors, however, it’s not that simple.

Aimco, the real estate investment group that owns the loans for Parkmerced, uses RealPage to inform their rental pricing and vacancy strategy. In a quarterly earnings report, Aimco describes its vacancy strategy, which “allows for the relatively frequent repricing of rents, a valuable tool during inflationary periods.” Parkmerced told investors that the reduction of in-person learning requirements at San Francisco State University directly contributed to lower demand at Parkmerced, a property with high vacancy rates. But Aimco soothed investors’ fears in 2021:

“San Francisco State University will return to full in-person learning this fall, increasing the demand for the apartments that serve as collateral for our loan.” Note that the language here concerns demand, which does not necessarily correspond with filling vacancies. The ProPublica piece on RealPage explains that they “urge apartment owners and managers to reduce supply while increasing price.”

One Parkmerced resident, David Thorne, says, “While our rent goes up a small percentage a year, all of the vacant apartments have gone up much, much higher.” This is partly due to San Francisco renters’ protections under rent-control policies, which restrict how much landlords can increase rent.

Thorne lived in a nightmarish situation. The property managers lost his rent check, which he deposited in their secure Rent Box Slot, and charged him late fees. When Thorne’s dog Hercules passed away, he asked Parcmerced to remove the pet rental fee and was told he couldn’t do so without a pet death certificate. Such certificates don’t exist in San Francisco, at least to the knowledge of Thorne’s vet. This isn’t the only time Parkmerced made this approach. Many years ago, they evicted a tenant for having a goldfish, which violates their pet policy.

In cities like Portland, renters face a 14.6% increase in their rent for 2023, leaving renters worried they wouldn’t be able to afford their homes. In San Francisco, landlords can increase rent by just 2.3%, but the San Francisco Rent Board clarifies that “There is no limit on the amount of rent a landlord may first charge the tenant when renting a vacant unit.” Landlords sometimes engage in illegal practices to encourage long-term tenants to move out to rent at a higher rate. San Franciscan renters have hordes of horror stories about such actions. State Bill 91 provided additional protection for renters during the pandemic, but the eviction moratorium ended. Where landlords were once content to find ways to raise the rent on tenants, it may be becoming more popular to cut the tenants out altogether.

Leaving it vacant: More profitable in the long-term?

“Having a tenant may just be more hassle than it’s worth,” explains Professor Steven Bourassa, Chair at the University of Washington’s Runstad Department of Real Estate. “Leave it vacant, let the price go up, sell it sometime in the future, and you’ve made a nice profit and don’t have to deal with tenants.”

Many renters seek housing in nearby Bay Area cities because of all these factors, but that might be changing. “The impact on prospective tenants is that there are a lot of tenants who don’t get to live in the places that they work or where their families are,” says Zamudio. “Folks are starting to come back to San Francisco because of the demand … This super-wealthy tenant, that tenant doesn’t exist anymore.” But landlords continue to hold out for wealthier tenants.

Parkmerced isn’t alone in having low occupancy. At The Oak, the Bertazzoni gas range costs about the same as the average rent in San Francisco. In the summer of 2022, it was named and shamed by the San Francisco Chronicle as an unusually empty building. Then there’s 2177 Third, which advertises exclusive residences. The main property has several units available, but the owners have other buildings. 2177 Third property manager’s portfolio includes The Chorus and The Landing. The Chorus has 59 empty units, which is 14% of the building. The Landing, which prides itself on being “one of San Francisco’s very first Airbnb-friendly buildings,” clocks in at a staggering 28% vacancy rate. These are just the units publicly listed as available.

Encouraging housing by discouraging vacancies

On November 8, San Franciscans will vote on Proposition M, which will tax property owners who keep units vacant for more than half of a given calendar year. Will this tax successfully address these issues?

“The housing market is set on artificially inflated prices,” said Zamudio. She said this is an important step in differentiating between supply and demand and what’s actually happening, which is a question of how San Francisco manages its current housing. “Housing here isn’t for shelter. It’s for profit.”

However, some are unsure. “For two reasons, I’m skeptical. One, I don’t see how you can enforce this, and two, I suspect, I don’t know, and maybe nobody knows, that the units that are being left vacant are more expensive,” Professor Bourassa cautions. According to the San Francisco Planning Department, that data is coming in 2023 or 2024 “as a result of a 2020 ordinance that requires landlords to report rental data.” Proponents of Prop M are keeping an eye on other cities with similar initiatives.

San Francisco is not the first to propose a tax on vacant units. Research from National Cheng-Kung University suggests that vacancy taxes can have a larger impact on the rental market as a whole, decreasing the cost of rent. Vancouver, Canada’s 2016 bill is not necessarily reducing housing costs, but it is its primary objective of reducing the vacancy rate. A report from the Barcelona Institute of Economics suggests that “by increasing the cost of keeping a unit vacant, a landlord will have more incentives to mobilize the unit and to increase the effort spent in finding a tenant or a buyer.” However, in all cases, economists and housing policy experts agree that the situation depends significantly on local factors.

In San Francisco, the Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office suggests that Prop M “should be considered as one of a number of policy tools to increase housing supply in San Francisco.” Urgent action is needed, and it will take many different policies to address the lack of affordable housing, especially given the new approaches introduced by software like RealPage.

“Landlords can decide how much to rent units out for,” Zamudio continues. “As long as landlords are allowed to speculate and to artificially inflate the price of a unit so that they can make a high return on their investment, then we’re going to see that the price of housing isn’t aligned with what folks get. It’s also not aligned with the right that all humans have to shelter and safety and dignity under a roof.”

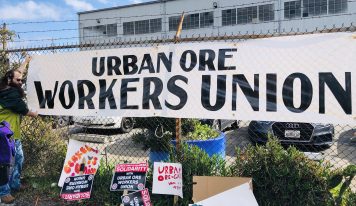

In response to data on the burgeoning number of units kept vacant, groups like Faith in Action and the San Francisco Democratic Socialists of America are hoping to copy the success of similar initiatives in Vancouver, Canada. The measure has received endorsements from a wide range of community groups, from the San Francisco Democratic Party to the Party for Socialism and Liberation’s Bay Area chapter.

At a rally on October 13, Minister Victor Floyd led the crowd in prayer and dedications at a shrine of marigolds on City Hall’s steps. “Knock, knock,” Floyd said. “Who’s there?” the crowd responded. Floyd, wearing round glasses and a clerical collar that peeked out from under his political shirt, answered deadpan, “Nobody. Nobody’s there in 60,000 homes in San Francisco.”

Photo by Sundry Photography

This story was updated on November 2, 2022, with minor edits for clarity.