We continue our series of blog posts from our Runstad Center Affiliate Fellows class of 2015, who recently traveled to Santiago, Chile, and Rio de Janeiro and Curitiba, Brazil. Recently, Thaisa Way explored the important role of public spaces in social housing. Here, she continues her exploration of the public realm with a look at the yards and courtyards of Santiago.

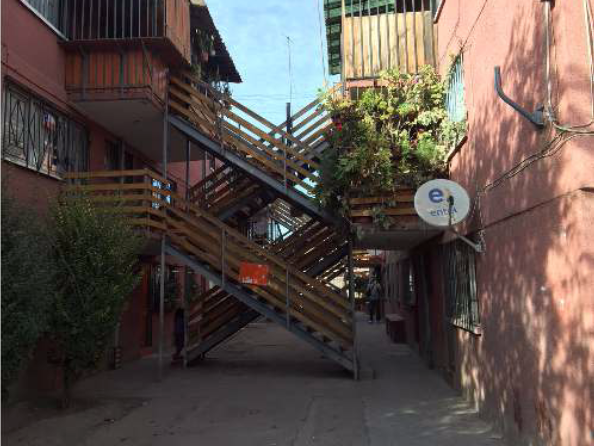

In a second scale of the public realm was the semi-private spaces of yards and courtyards. These spaces were found in university buildings such as the UDP School of Architecture where an interior courtyard beckoned one into the building from the street, and in the spaces between the social housing in one of the poorest neighborhoods in northeast Santiago. In the case of the former, the open-air courtyard and the access provided to a roof garden integrates out of door spaces for all in the community. These spaces were used for maker spaces, messy spaces, and socializing spaces. Of course this is easier in the climate of Santiago than a place like Seattle, but nonetheless the importance of finding ways to incorporate safe and welcoming out of door spaces in our buildings and neighborhoods seems worth the creative efforts it requires. It was the courtyards in the social housing that were a real source of inspiration- here in a community of extremely “efficient” housing, about 300 -600 sq feet per family, the out of door shared spaces provided a living room for the immediate families. In one that we visited roses, geraniums, and jasmine grew in neatly defined flower beds while the primary area was a swept yard, clean and welcoming. Talking with a resident it was obvious the courtyard was a source of pride and joy. It was not big, and it was shared with 12 households and yet it was a place where in the midst of a zone where gang fights were common and trash piles up on the streets, this clear, swept, flowered landscape was a respite and a shared resource.

A similar need for diverse out of door spaces throughout Santiago was met in multiple ways throughout the city creating a remarkable urban landscape. Along the now polluted river of Mapucho, there is a river promenade often expanding to become a full fledged park with playgrounds, fountains, and benches. On the ancient volcanic hills parks were built that allow one to see the city from above- some very formally such as San Cristobal, others more informally such as Castillo Hildago and St. Lucia. Eating out of doors is common throughout the city- whether on a terrace or spilling onto the sidewalk or picnicking in the park- drinking was allowed or at least tolerated as well making for a dynamic public comprised of young, old, active, contemplative, boisterous, and romantic. When the bicyclists and runners took over many of the broad streets on a Sunday morning, the old city could be experienced as a broad and generous urban landscape. Tree lined avenues marked the major boulevards while a diversity of street trees, flower boxes, and hedges added life and vitality to the smaller streets and pedestrian paths. On the latter, it was the generosity of the pedestrian spaces that also nurtured the public realm – whether the closed streets (what we call the pedestrian malls) or the passageways or the plazas, these landscapes encouraged the sharing city. Santiago was an impressive urban landscape – generally vibrant and yes messy, yes chaotic, and yes green and alive with a public realm just as dynamic.