This is the fifth in a series of blog posts from our Runstad Center Affiliate Fellows class of 2015, who have just returned from their travels to Santiago, Chile, and Rio de Janeiro and Curitiba, Brazil.

Hi there! I’m Maiko, and I’m a Runstad Affiliate Fellow. Welcome to my introductory blog. Yes, I haven’t done this before. I come from a community development background, and that’s the lens by which I see things. I feel extremely lucky to have this opportunity to travel and learn with my fellow Fellows. You learn much when you’re traveling with people, you know?

Enough about me, on to Santiago de Chile!

If you’re reading this, chances are that you’ve already read Kate Simonen‘s Segregated Santiago piece. That comment – that Santiago is a very segregated city, with strong concerns around income inequality – came up repeatedly amongst almost everyone with which we spoke. Head’s up, it’ll come up again near the end of this piece.

Another comment that came up with everyone: quantity versus quality in affordable housing. In fact, these same bits came up with such frequency that for a second, I started thinking that somehow everyone we spoke with had the same talking points… wow, perhaps they had to recite these phrases to be able to work in Santiago as an architect / urban designer / planner! Granted, we were on a tight schedule and talked with people who were all well educated, with most, if not all, living and studying in the US. They were roughly close in age – early 40s to perhaps upper 50s. We had, we think, met them all through one person.

My theory was blown when we went to dinner with a couple who were family friends one of us travelers. They are also well educated, but they worked in public health and public policy. And they said the same exact things. So perhaps that’s a sign that as a country, they are much more unified in their beliefs? This great couple also asked us how could we just talk about the housing without seeing it? They fixed that for us – that’s Kate’s next blog….

Chile has been working towards the provision of housing for its residents (citizens or not) as a major policy since 1973, the year Gen. Pinochet gained control of the country in a coup over the communist Allende government. In case you ever wondered about it, Chileans knew that the coup was about to happen, and that our government wanted it enough to pay for it. We heard that families lived in fear for the 15+ years Pinochet was president, as well as the 8 years after the transition to democracy when Pinochet was still Commander in Chief of the military. We heard that for the well-off, children were told early not to speak with anyone outside the house, especially about contingency plans – if the living room curtains were closed, Dad was to not come home and plans were put into action. We heard that if you were not well off, you witnessed military guards coming into your neighborhood and shooting your blue collar neighbors to death because they were on strike. Regardless of class, it seems that almost everyone feared the night. Having people tell me that my country caused strong and undeniable internalized feelings of guilt and shame.

Back to housing…. because of the work I do in Seattle, I was extremely interested in affordable housing in Chile. At the start of Pinochet’s rule, 25% of Chileans were not housed well – no one used the term homeless, so I **think** they may have been homeless or not not living in sanitary conditions. That number has decreased to under 3%.

If the goal is shelter, sounds like huge progress. The original goal, though, wasn’t shelter. The original goal was to stimulate the banking and construction industries as it seems they were pretty dormant under the previous communist government. It was one of the signs to the US, and the developed world, that this dictatorship had kickstarted the economy and was doing something good for its people… and maybe the US and others would be generally okay because the country would not be a “falling domino” to communists, had Chicago-educated Chileans running this capitalist society….and maybe we could overlook human rights violations.

Families were given vouchers to buy their unit, with the cost to the families dependent on their ability to pay; the first families to receive these vouchers could pay something, and had to borrow funds from (as well as place their savings into) the newly privatized banks. Later adjustments in this policy – and it seems that Chileans tweak their policies with some regularity – allowed families with no funds to purchase as well.

This kicked off the QUANTITY phase… And although it appears to have been that stimulus those industries needed at the time, there were a host of other issues that have arisen. Chileans know and recognize this, and now the general theme is QUALITY. And some of these issues and challenges sound familiar.

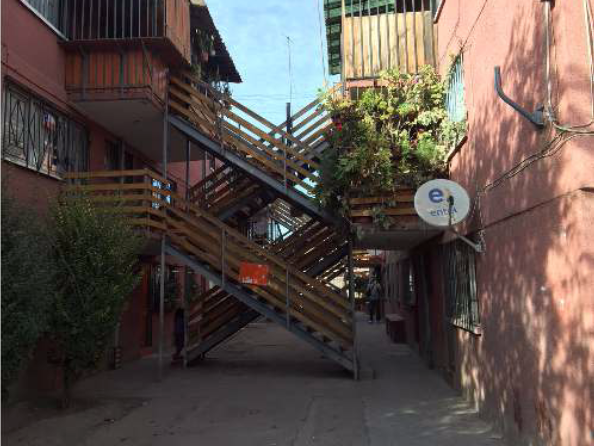

• these new units were in locations often far away from where families were living, putting them literally hours away from their communities and employment. By putting a class of people together, it made it easier for the Pinochet government to keep track of “those people”. Over time, it concentrated poverty and Chileans acknowledge that these social problems – drug dealing, sexual abuse, domestic violence to name a few that came up – are not good for the country.

• the quality of the units were not consistent over time. Some builders did shoddy work, and consumer protections and rights aren’t well understood. The free market was not balanced by government.

• having a roof over one’s head is not enough – that people need sidewalks, green space, schools, and good transportation to be good Chileans. When newer communities are built, these other key elements must be included in the development.

• proximity to a wider range of incomes is important in order to break down income segregation. In the urban environment, income inequality is of concern. In our conversations, our hosts reflected nostalgically on having their bicycle repair guy live nearby or discussing how you really couldn’t tell their adult children’s upperclass upbringing through their clothes and lifestyle. The government is exploring what, when explained to me, was inclusionary zoning. Very specifically, we discussed a housing project where they were allowing increased density if the developer would add affordable units. The government received development proposals placing market rate units in a 6 story building, with the affordable units in a neighboring 4 story unit (4 story units do not require an elevator and are thus cheaper). They have not outrightly accepted or denied the proposals as they are considering the implications.

In my mind, housing is a means to an ends – it is used as a tool for a bigger policy. As we fly from Santiago to Rio de Janeiro, I’m noodling with what is it that Seattlites want to achieve through housing. I know we say a lot of the same things I’ve heard in Chile – but do we really believe it? And if we do, what price are we individually wiling to pay for that belief? I appreciate their willingness to admit shortcomings of their policies, the need for adjustments, and this desire to move their country forward. Can we do the same?